|

|

Post by tusses on Jun 10, 2008 11:57:16 GMT

OK - being 'Norm' taught, I never really picked up a hand plane.

Now I am starting to learn how to tune them and learn how they work, I got to thinking ..

in power tool terms - the infeed is level with the outfeed, and the blade is lower and cuts the wood.

now if I set my 6" jointer (powered one) up like this, it wouldn't work !

so why does it work with a hand plane ? - or doesn't it ? !

|

|

|

|

Post by mrgrimsdale on Jun 10, 2008 12:24:05 GMT

OK - being 'Norm' taught, I never really picked up a hand plane. Now I am starting to learn how to tune them and learn how they work, I got to thinking .. in power tool terms - the infeed is level with the outfeed, and the blade is lower and cuts the wood. now if I set my 6" jointer (powered one) up like this, it wouldn't work ! so why does it work with a hand plane ? - or doesn't it ? ! The power plane would work like a hand plane if you set it up the same i.e. infeed/outfeed in line with blade projecting sllghtly. But not vice versa as you wouldn't get the cutting power just by pushing a fixed blade forwards, if using the full width of the blade that is. That's why you need a camber on any hand plane for surfacing stuff wider than its blade - it slices out a shallow scoop, not the full width. Though there are chamfer planes with adjustable beds which do work, because they only take off a smidgin, and I guess something similar would work on board edges. cheers Jacob |

|

jay

Junior Member

Posts: 80

|

Post by jay on Jun 10, 2008 12:52:42 GMT

In that respect hand planes don't work. If you just apply plane to wood and go pushpushpush you'll end up with an everso slightly convex surface. You need to compensate by taking a few extra 'stopped' strokes out the middle before taking a final swish or two of the whole length if you want a perfect mating surface. (short planes like your number 4 aren't much cop at perfectly flat anyway, you want a longer plane for that sort of thing)

Good/Bad technique can help/hinder - if you start the stroke applying downward pressure at the heel and end the stroke applying pressure to the toe you'll exaggerate the problem. Apply pressure to the toe at the start of the cut and finish with pressure on the heel (think scooping as you plane) and you'll eliminate some of the potential for the convex problem.

|

|

|

|

Post by tusses on Jun 10, 2008 14:05:11 GMT

shallow scooping makes sense  Ta .... back to the grind stone ! |

|

|

|

Post by mrgrimsdale on Jun 10, 2008 14:36:44 GMT

shallow scooping makes sense  Ta .... back to the grind stone ! Yers. Scoop both ways - along, as Jay says, and across, due to blade camber, with shaving tapering to zero at edges |

|

|

|

Post by engineerone on Jun 10, 2008 19:47:07 GMT

basci thing to remember is that when you use a planer/thicknesser, you are pushing the front of the wood over the cutter, so it is slightly less deep, hence the need to re set the outfeed table. whereas, with a hand plane, the plane in front of the body is in contact with the wood before the blade is. however a recent article with american writer and woodworker michael dunbar suggests that you can hold the plane in a vice, or in your hand, and push short pieces of wood over the blade. it is not as easy as it sounds, but does work too. paul  |

|

|

|

Post by tusses on Jun 10, 2008 20:11:00 GMT

yes but - the front is level with the back ... so , if you put the front on the wood and cut - you have removed wood so the back of the plane has nothing to rest on without dropping and lifting the front slightly

the scoupy dish thing makes sense as the plane bed is supported on the wood at the edges around the scouped out bit

hmm..... just thought - the scoupy dish thing goes to pot if you are planing an edge !

as Jay suggested - the wood wont be flat unless you compensate for this

|

|

|

|

Post by engineerone on Jun 10, 2008 21:47:06 GMT

ok so you want complicated ;D basic practice is to press down on the front of the plane as you start at the beginning of the wood, then as you get to the other end, you put more weight on the rear. but of more importance to understand is that initially even a par board is not flat, because it was machined by mechanical means, the blade only hits the high points. which is why roughing planes are longer. as the board gets flatter, you want less distance between the front and back of the plane. but also why you reduce the distance the blade sticks out. finally what the hell, it works  ;D   paul  |

|

jay

Junior Member

Posts: 80

|

Post by jay on Jun 10, 2008 22:11:23 GMT

In practice the fractionally convex surface you get from a hand plane will be good enough a lot of the time. For show faces it's not really a problem. If you need long mating surfaces (gluing boards together by the edges for example) it's not so great. It's those occasions that you need to be taking a few extra stopped shavings out the middle of the edge to eliminate the hill.

|

|

|

|

Post by nickw on Jun 11, 2008 11:48:37 GMT

Sorry Jay, but you've not quite got it right. Because a plane blade sticks out of the bottom of a (more or less) flat sole, you will get a slightly concave (depending on how far the blade is protruding, and assuming that the board is more than twice the length of the plane) result. On edges, taking stopped shavings exaggerates this giving a more positive sprung edge for jointing.

|

|

|

|

Post by paulchapman on Jun 11, 2008 13:08:20 GMT

Because a plane blade sticks out of the bottom of a (more or less) flat sole, you will get a slightly concave (depending on how far the blade is protruding, and assuming that the board is more than twice the length of the plane) result. On edges, taking stopped shavings exaggerates this giving a more positive sprung edge for jointing. I don't think that's right, Nick. In my experience, if you keep planing a piece of wood along its length, you will eventually plane it into a curve, with the two ends lower than the middle, which is convex - like the outside of a circle. What you need to do to overcome this, is to try to plane the wood hollow, which is the reason for taking stop shavings. Cheers  Paul |

|

|

|

Post by nickw on Jun 12, 2008 20:18:57 GMT

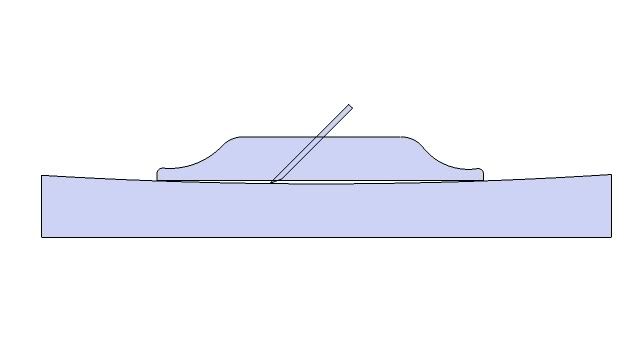

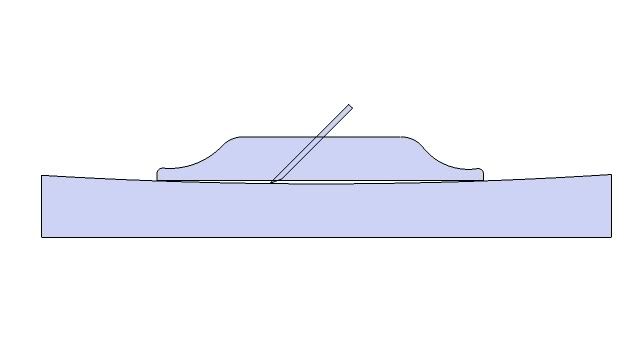

The only thing a flat soled plane, with a blade sticking out of the bottom can do is make a hollow surface. In the pic below the blade protrusion is exaggerated to make the situation clearer.  It is very easy to make the beginning and end of the piece convex if you do not apply pressure to the toe of the plane at the beginning, and to the heel at the end of the pass, and if the timber is relatively short the whole thing will end up convex. However if you keep the sole firmly in contact with the timber the planed surface will end up very slightly hollow along its length. If you're not getting that then either you need to perfect your technique, or your plane's sole is not flat (you have a fixed radius compass plane). If we're being really picky I think there may be some second-order effect at the beginning of the stroke from the point where the blade first enters into the timber until the sole behind it comes into contact with the timber, and a similar one at the end of the stroke as the toe becomes non-functional as a support. |

|

|

|

Post by mrgrimsdale on Jun 13, 2008 15:45:08 GMT

Confused here.

Your drawing shows a concave surface, which would appear to be what you should expect if you don't offset it in some way. Makes sense - but the opposite happens: if I plane away regardless, to get down to the line quickly, the work tends to end up convex and I have to take more from the middle.

Whatever the logic, it doesn't work that way necessarily. If frinstance you start of with a slightly convex surface you can increase this convexity as you take off more at each end, as the toe or the heel drops.

There's no escaping from having to look closely at what you are doing and adjusting accordingly, rather than relying on the plane itself, as you might a machine.

cheers

Jacob

|

|

jay

Junior Member

Posts: 80

|

Post by jay on Jun 13, 2008 16:42:16 GMT

The problem I see with your diagram Nick, is that your plane (your's is much posher than mine by the way - kudos) is about to slice off the high spots on either end. A few more swishes down the road and it'll make a tiny little hill. Give in to the convex side Nick, it is your destiny. |

|

|

|

Post by engineerone on Jun 13, 2008 20:58:48 GMT

off that part of the topic, but i was reminded to day that a really useful plane to buy is a rebate 60 1/2 and ln do a nice one. below a ton i think but containing all the nice things to push you down the slope ;D paul  |

|

|

|

Post by nickw on Jun 13, 2008 21:53:56 GMT

Jay,

It might just take a small bite out of the very end as the toe passes over the end of the timber, but the majority of the length of the timber will remain concave. End conditions will be slightly different from the majority of the length of the timber.

I've just done some tests, to make sure I'm not kidding myself, removing about 1/4" from the edge of an 18" long board.

My No5 with sole flattened in Mr Charlesworth's workshop (though admittedly a few years ago now) produces a hollow in the length that is just visible against a strong light tested against my engineeer's straight edge.

My No 6 produces a slight crown - BUT - it has only recently come into my posession (having come, via an Uncle from my Grandfather) and I haven't got round to flattening it properly yet. Testing its sole against a straight edge it is indeed about 2 thou hollow in its length.

Check your planes, and check your technique.

|

|

|

|

Post by mrgrimsdale on Jun 14, 2008 7:22:36 GMT

The only thing a flat soled plane, with a blade sticking out of the bottom can do is make a hollow surface. In the pic below the blade protrusion is exaggerated to make the situation clearer.  snip OK so if the workpiece in the drawing had no start/end, i.e. not infinite, but circular, then the plane as shown would not cut at all, but merely float around the curve - defined by the triangle formed by the nose/heel/blade. It would only cut if the blade was extended for each pass - to start the cut - and then retracted as the heel drops in to the new cut (it's quite complicated) If the workpiece was short - then at the start of each cut the blade would cut it's full depth, i.e. the front of the mouth would sit on the end of the piece, whatever the curve or length of the sole. However, as the plane moves forwards the blade would lift, as the back part of the sole comes to bear on the workpiece. It would cut progressively shallower. The opposite would happen as the plane leaves the end - as the front of the sole goes over the end, the blade is lowered, cutting deeper and finishing at its full extension. So the result is just what is so often described - a convex tendency. ;D ;D cheers Jacob |

|

jay

Junior Member

Posts: 80

|

Post by jay on Jun 14, 2008 7:52:09 GMT

I suspect Nick is applying so much downward pressure that his bench and workpiece are deforming under the strain, resulting in concavity.

|

|

|

|

Post by engineerone on Jun 14, 2008 9:10:58 GMT

and we wonder why people are scared of hand tools ;D had i known it was this complex    according to some old maths i remember a straight line is only a curve of infinite radius anyway  however somehow pushing down at the front when you start and at the back when you finish seems to give me bits of wood which my engineers ruler seem to think are pretty flat  paul  |

|

|

|

Post by paulchapman on Jun 14, 2008 9:39:09 GMT

A good way to test it out is to put two pieces of wood together and plane the edges (how I normally joint boards if they are not too thick). When you put the edges together, it will emphasise how much curvature there is at the ends if you haven't taken stop shavings. Either way it doesn't really matter - whatever works for you and all that ;D Cheers  Paul |

|

|

|

Post by dirtydeeds on Jun 14, 2008 21:29:14 GMT

the question was, how does a (hand) plane work

the answer is a hand plane has a flat surface from which a blade protrudes, before you do any planing the plane effectivly rocks on the blade

as you push the plane forward the blade digs into the wood

the flat surface in front of the blade then stops the blade from driving any deeper than the blade protrudes

as the plane moves further forward the flat surface behind the blade now comes into contact with the wood (as well as the front)

the blade now cannot go any deeper

the degree of curvature that has been mentioned is relative to the length of the plane

a try plane / jointer can be as long as 24 inches

its length enables it to remove the high spots first and come to a fully flat surface

the final surface of a try plane has a much larger radius than say a block plane or a chisel plane

|

|

|

|

Post by sainty on Jun 15, 2008 0:43:14 GMT

Ok, I've often thought about this myself, and an evening home alone with sketchup (rock and roll!) leads me to the following long and winding explanation. Conclusion 1. If you start with a straight piece of timber you will end up with a straight piece of timber. 2. If you start with a concave piece of timber, you will end up with a straight piece of timber. 3 If you start with a convex piece of timber you will end up with a convex piece of timber. AssumptionsThis of course is all theoretical and makes the following assumptions: The plane that is used is perfectly flat. This is reasonable in the real world to acceptable tolerances The plane blade is flat and parallel to the sole of the plane. Unlikely in reality where a cambered blade is the preference. However as long as the centre of the blade (or the part with the largest projection from the sole of the plane) is kept in the centre of the timber it will have the same effect. If the blade is cambered, it must be uniformly cambered. Perfect technique. As the plane is presented to the timber, pressure is applied down between the toe and the blade. As the whole of the plane is on the timber equal pressure is transferred from the toe to the heel of the plane. As the plane leaves the timber, pressure is applied between the blade and the heel of the plane. Presumably this could be achieved but it is unlikey to happen consistently. DrawingsStraight Timber 1. Before cut is taken, pressure is applied between the toe and the blade, the blade projects below timber  2. During the cut pressure is still applied between the toe and the blade, the depth of cut is determined by the projection of the blade  3. As the cut continues, pressure is transferred to the heel of the plane. The plane will tip to the back but this shouldn't affect the depth of the cut which is determined by the projection from the sole of the plane directly in front of the blade.  4. The cut continues, until the end of the piece of the timber with pressure between the blade and the heel.  Result: Flat piece of timber Concave Timber: 1 The same process applies to planing a concave piece of timber, the first pass will remove the high spots at the beginning and the end.    The centre of the timber isn't touched in the first pass, further passes can then be taken until the timber becomes straight. Convex Timber: Ok so I haven't done the diagrams for this. Basically it is almost impossible to plane a piece of convex timber straight. Unless your technique is such that you can hold a plane in the same plane (apologies) consistently. The first pass to take only the highest point of the timber, continuing until you have a straight reference surface from which to place the plane for further cuts. The work around would be to take stop shavings until you have a concave surface nad then plane as normal. Well thats it. Hope it makes interesting reading to someone, it certainly clears thing up in my mind. Having gone through this process, I am reminded of David Charlesworths DVD on hand planing technique. Definitely worth a look if you want a demonstration planing technique. Rgds Sainty |

|

jay

Junior Member

Posts: 80

|

Post by jay on Jun 15, 2008 0:58:16 GMT

oh were it that simple. Key to the convex problem is to note that the heel follows in the cut (let's stick to planing edges, it gets worse with faces) and the cutting iron follows the mouth. Cutting depth is not constant, but follows an arc whose aspect is defined by the angle described by mouth and heel. I'd try to explain more fully, but frankly it makes my head go pop; that's a job for someone with a maths GCSE. I suspect segments (line and circle) are significant.

The upshot is that planing your straight piece of timber would result in a minutely convex piece with the right hand side slightly shallower then the left.

|

|

|

|

Post by mrgrimsdale on Jun 15, 2008 7:10:25 GMT

Hmm thats all jolly interesting, well done with the drawings sainty!

No its easier than that - all you have to do is start the cut in from the end, and finish it before you reach the other end. So the untouched end bits become the reference points as the hill between them reduces.

cheers

Jacob

|

|

|

|

Post by modernist on Jun 15, 2008 7:21:15 GMT

So what we need are planes with dovetail slide, like a felder surfacer, behind the mouth so the rear sole moves down with the blade.

I'm sure LN will knock one up shortly sor a modest fee ;D

Brian

|

|